Platforms

| Case: Moon, Y., “Uber: Changing The Way The World Moves” Harvard Business School Case No. 316-101, January 2017

Case preparation: Uber, June 2022 |

Textbook Reading: Chapter 5 (Section 5.3; pp. 145-149)

- The world’s largest retailer, Alibaba, has no stock

- The world’s largest taxi company, Uber, owns no cars

- AirBnB own no hotels

- Facebook produce little media content

Platforms are dominating an increasing area of the digital landscape and generate revenue through:

- Subscription fees

- Commissions

- The monetization of attention

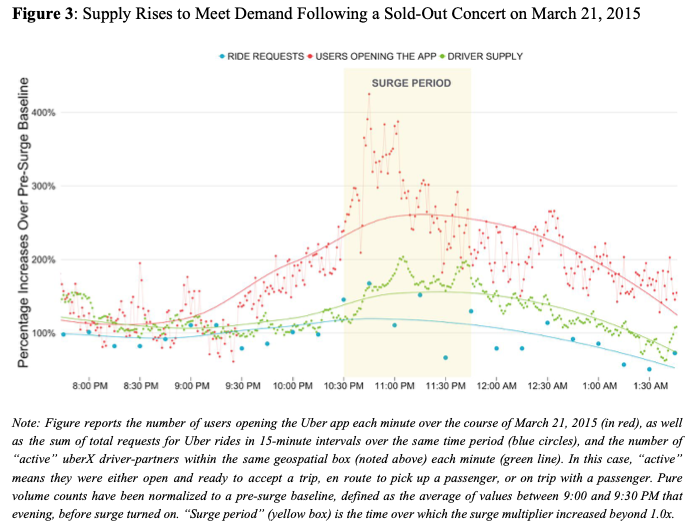

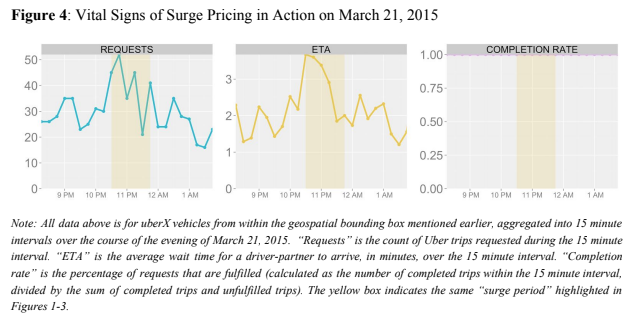

This case study looks at the effect of Ariana Grande’s sell out concert at Madison Square Garden in 2015. The chart below is fascinating. The red line is a reflection of demand, showing how many people are opening the app (presumably because they are hoping to get a ride). The peak at the end of the concert is obvious and increases by a factor of 4. Ordinarily, one might expect massive increases in wait times and a shortage of drivers. However Uber’s surge pricing algorithm increased the fare which enticed more drivers to be available. This is the green line.

The consequence of the increase in supply, to deal with the heightened demand, was an extra minute of wait time but no drop off in the number of completed rides. How amazing!

You can read the full article here:

- Hall, J., Kendrick, C., and Nosko, C., “The Effects of Uber’s Surge Pricing: A Case Study“, September 2015

In 2023 I published an academic article on how cultural economics helps us to categorise and understand new entrants such as Uber. I find that reducing entry barriers and less exclusion are key factors in a dynamic market order. Here is Elizabeth Warren emphasising the distinction between employees and contractors (note: I think she’s wrong):

Big corporations are "misclassifying" workers as contractors to cheat them of their benefits (I'm looking at you, @Uber).

It's wrong. But thanks to a new rule by @POTUS, workers can now fight back. pic.twitter.com/agUx1Vt991

— Elizabeth Warren (@SenWarren) January 24, 2024

In this Vanity Fair article, Uber co-founder Travis Kalanick defends surge pricing:

“You want supply to always be full, and you use price to basically either bring more supply on or get more supply off, or get more demand in the system or get some demand out,” he lectures like a professor. “It’s classic Econ 101.”

Don’t forget – waiting in line is just another form of surge pricing:

Another upside of ride sharing apps is a reduction in drink driving. According to one study,

Our results imply that ridesharing has decreased U.S. traffic fatalities by 5.2% in areas where it operates. The annual life-saving benefits are $6.8 billion.

An excellent article on the incentives of platform industries is “The Host’s Dilemma” by Jonathan Barnett. He argues that platform providers face a trade off between being open (and generating users) and regulating access (to monetise).

Recommended reading:

- Barnett, J.M., The Hosts Dilemma, Harvard Law Review

| Learning Objectives: Peer-to-peer markets, Ethical implications of disruptive business models

Cutting edge theory: An economic analysis of platforms Spotlight on sustainability: Employee welfare |

I also thinks it’s important to recognise that the general public typically overestimate the profit margins of large companies (

I also thinks it’s important to recognise that the general public typically overestimate the profit margins of large companies (