Witness transition

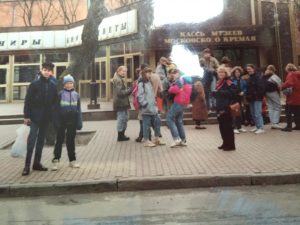

Here I am on a school exchange to Russia in the Spring of 1992:

Moscow, April 1992

That trip prompted a fascination with alternative economic systems and the process by which a country can transition from communism to capitalism. This page is a collection of resources that have nurtured and fuelled my interest in post-Soviet transition.

Documentaries

Traumazone, by Adam Curtis – this collection of BBC archival footage provides a fascinating and absorbing insight into how life changed for ordinary citizens of the Soviet Union, from 1985 through 1999.

For more see here: https://www.filmsforaction.org/watch/traumazone-2022/. I also recommend Chris Snowdon’s review.

Excerpt from a 1985 documentary:

Soviet Moscow. Excerpt from 1985 documentary film. pic.twitter.com/E0rnliv3fe

— Soviet Visuals (@sovietvisuals) March 7, 2024

Collective (2020) – a quite stunning look at how public officials attempt to restore trust, and how investigative journalists pursue justice, for the victims of the 2015 Romanian nightclub fire.

Short video

Bald and Bankrupt – a British vlogger who travels around the former Soviet Union providing a glimpse at the legacy of communism. I particularly liked this video, filmed one day before the Russian invasion of Ukraine:

Flying over Berlin in 1991 – aerial shots taken by a helicopter

Berlin 1990 the end of the war (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) – home movies shot by Derek Williams, who was in Berlin to see the Pink Floyd concert.

Me visiting the Berlin wall in 2023:

Movies

Good Bye Lenin! (2003) – Set in East Berlin, a woman falls into a coma and misses the fall of the Berlin Wall. When she awakens her children don’t want to shock her, and attempt to screen the economic changes occurring outside the bedroom window. This is an entertaining but poignant demonstration of the transition process and alternative economic systems.

For more movies, see my Shin Film List.

Podcast interviews

- #301 – Jack Barsky: KGB Spy, Lex Fridman podcast – A fascinating background on Cold War intelligence services.

- #349 – Bhaskar Sunkara: The Case for Socialism, Lex Fridman podcast – Bhasker calls himself a “democratic socialist” but I maintain that this is an aspirational label rather than one that can be understood in theory or demonstrated in practice. While the left attempt to grapple with their history of actually-existing-socialism, I think it is wise to go with capitalism, which is the only system that seems to work so far. It’s also notable that Bhaskar’s magazine, The Jacobin, is well designed and popular, but routinely misrepresents free market economics and is geared towards activism rather than serious enquiry.

- Ep. 7: Eric Mack — Why Not Socialism?, The Curious Task, September 18th 2009 – regardless of collectivist aspirations, this interview recognises that the essence of socialism is a centrally planned economy. Mack draw uses camping trips as a model of “the good society” but I think this suffers from three flaws. When it comes to a camping trip, the participants already know each other; everyone has consented to participate; and there’s no need to create resources (camping trips are primarily about consumption rather than production. If you want to drink a beer, you bring it with you having paid for it with previously expended labour). This reveals that most socialist visions are utopian and don’t solve the real world problems of how to create human flourishing in an extended social order. Ultimately, socialism is a collectivist philosophy that requires subjection of the individual to the whole. Therefore it should be rejected by anyone whose fundamental concern is the dignity and sanctity of the individual.

- The Road to Socialism and Back — Peter Boettke & Rosolino Candela, Hayek Program Podcast, August 23rd 2023 – this interview makes clear that the main tragedy of socialism is that it is unintended. The results are inconsistent with the stated goals of the advocates, implying the problem is an intellectual one. Hence the need for scholarly enquiry and public education. They also recognise that a centrally planned economy may function better than a market economy during times of war, but this should not be the model. After all, a stable peace is as important a social objective as greater wealth. This interview also captures Pete Boettke’s biggest contribution to economics: in the absence of the “three P’s” of property, prices, and profit and loss you have to rely on political power to allocate resources. Therefore, a socialist society will be riddled with rent-seeking and the other inefficiencies associated with “politics without romance“, giving rise to the nomenklatura and priviledge. He also makes the point that prices are embedded in institutions, and institutions are embedded in broader social relations. We therefore need to understand law, politics and society, as a coherent social science. Finally, I like the point made that a free market economy lets ordinary people do extraordinary things. It doesn’t rely on extra ordinary people controlling and directing a vast bureaucracy.

Written ethnography

Here are some recommended books that uncover the impact of transition on the daily life of ordinary people:

- The unmaking of Soviet life: Everyday economies after socialism, by Caroline Humphrey, 2002

- Domesticating revolution: From socialist reform to ambivalent transition in a Bulgarian Village, by Gerald Creed, 2007

- Market dreams: Gender, class and capitalism in the Czech Republic, by Elaine Weiner, 2007

- Crisis and the everyday in post-socialist Moscow, by Olga Shevchenko, 2008

- Getting by in postsocialist Romania: Labor, the body, and working-class culture, by David Kideckel, 2008

- Needed by nobody: Homelessness and mumanness in post-socialist Russia, by Tova Hojdestrand, 2009

- Secondhand time: The last of the Soviets, by Svetlana Alexievich, 2013

Online learning

BBC Bitesize has a module on the Cold War, which deals with the fall of communism. See here.

Here is my webpage about The Museum of Neoliberalism.

My stuff

- I devoted a section of Chapter 12 of my Managerial Economics textbook to transition. You can read it for free here.

Here are two videos defining capitalism and liberal democracy:

“This isn’t the Wild West.”

“You got that right. This is the timid West. We need to roll the clock back.”

Jack Reacher, Gone Tomorrow