Online learning

Also see: Classroom Tech and Making videos

The covid-19 pandemic has prompted a mass transition from in class tuition to virtual learning. It’s an incredible pedagogical experiment, and I’m intrigued as to how it will play out. ESCP Business School was an early mover – our Turin campus made a complete switch online on February 23rd. I’m the Teaching & Learning coordinator for our London campus, and we have been anticipating and managing as smooth a transition as possible since then. We went fully online on March 16th.

This crisis situation has prompted an immediate action, but it reflects a deeper trend away from the classroom. I feel well placed to react because I’ve made online learning a key part of my professional strategy. In 2016 I launched an online Managerial Economics course as part of ESCP’s “Executive Master in International Business” (EMIB). Following that, I added a new online course every year, such that in 2019/20 my online teaching exceeded my in class instruction. I am a digitally minded person, and have loved the opportunity to develop courses that help me to recognise more clearly the value of being physically present. For me at least, those two forms of teaching are complementary and teasing out how they interact has been satisfying.

[This intro was written March 15th 2020. The rest of the article has been modified since then.]

It’s not obvious that teachers have the right skillset to create online courses.

The key skillset for a lecturer:

- Knowledge of the content

- Personable delivery

- Ability to grade exams

The key skillset for an online instructor:

- Ability to curate content

- Aptitude with alternative technologies

- Choice of assessment

So instructors should think carefully before attempting to move online. It takes preparation and experience, and may be detrimental to in class instruction.

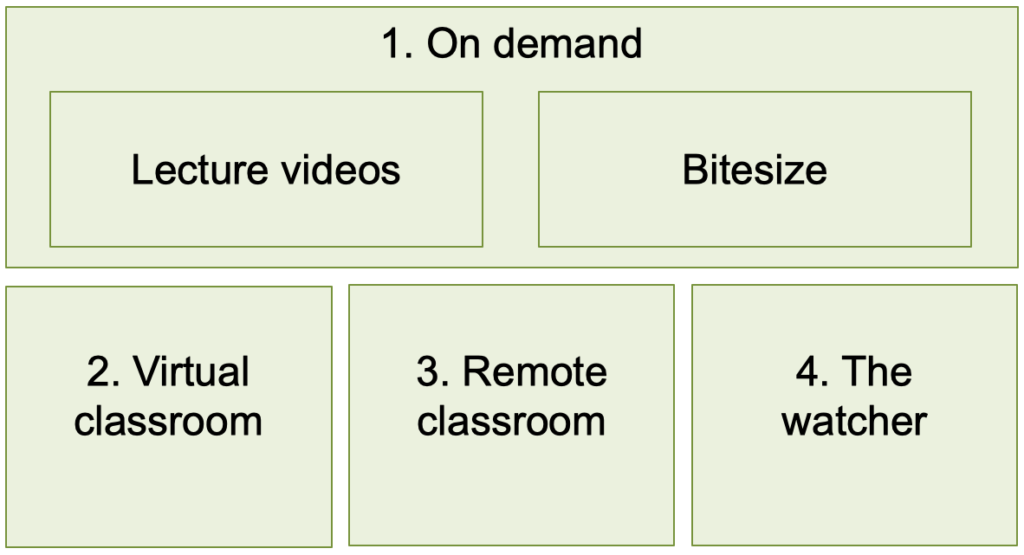

I see a few basic models for online learning:

Model 1: Your own pace (on demand)

These type of courses remove students from the dreaded (and stupid) syllabus and allow us to package a course into engaging digital content. I think there are two types of on demand courses.

1a. Lecture video

The first is a simple ~30 minute lecture + quiz. The platforms that I use and recommend are Coursera and Udemy. I am also impressed by edX. I’ve built a course on Teachable, but it’s quite expensive. The good thing about this model is that it is simple to create and the time commitment can be easily calculated. The bad thing is that there can be a temptation to simply record existing lecture content, and this can be boring.

1b. Short content (bitesize)

The other on demand model is a mixture of different media, with much shorter videos. I used to think that the model for this was a simple process:

- Read this

- Watch this

- Listen to this

- Do this

However in my experience this sends the students off into too many directions. An advantage of an online course should be that they can consume the material in the same “sitting”. Either have extensive video content (e.g. the first option, above); use of articles (which are typically consumed on a tablet, or as hard copies); or everything audio based (so they can do things on the move via a podcasting app). Although I think it’s important to provide a range of content I believe that the course itself should be delivered through a single user interface.

For ESCP enrolled courses I use our existing learning management system, which is Blackboard, because it integrates with grading and students already have password protected access. Some courses I run are via Canvas, which is substantially better. I still find it surprising that it’s non-enrolled programmes that provide an effective user experience, and elite business schools that use glorified file management systems.

The way to incorporate short, mixed content through a traditional LMS is scorm packages. I have tried multiple versions (including iSpring and isEazy) but do not find them effective. They are hard to create and edit and don’t lend themselves to a clear user journey. I have recently experimented with LearnDash (which is a WordPress plug in) and I find it an effective way to present short digital content in a structured and visually appealing way.

For economics instruction, I like the Foundation for Economic Education, but by far the best options are run by Marginal Revolution University. In particular these courses:

- MR University Microeconomics – a 12 hour course with exam

- MR University Macroeconomics – a 10 hour course

You could also do a lot worse than simply watching Jacob Clifford’s YouTube channel.

For some non economics courses, consider:

- The US Holocaust Museum has a module on Ethical Leadership

- Justice, by Harvard’s Michael Sandel

- The ‘God and the Good Life‘ course at Notre Dame does a great job at presenting an online syllabus.

- The BBC’s “History of Ideas” are lovely.

- Here are 250 Ivy League courses you can take online right now for free (also see this thread)

Finally, my own course on Analytics (including Numeracy Skills Bootcamp; An Introduction to Game Theory; and Collecting and Presenting Data) follows a student led model. As does my Blended GMP courses on Microeconomics and Macroeconomics. A key thing to ensure is a structure, such that students pass through the modules on an appropriate timescale and remain motivated.

Model 2: Virtual classroom

When built well, student led classes can be very effective. But they can be a challenge to ensure consistent student engagement. It’s no surprise therefore that for many traditional courses that are having to transfer online, the prevailing course structure is important. The need to retain a timetable, and get students to interact, more closely replicates their previous experience. Don’t forget, one reason people pay for gym membership is the discipline of going to the gym. If students wanted a DIY alternative they’d already have chosen that, and they would have saved a large amount of money in doing so. So how do you keep the class together?

- HBX Core Curriculum – an 8-18 week programme utilising HBX Live. Around 150 study hours. For an example of a virtual group discussion – see Michael Sandel’s course “The Global Philosopher”.

- Blackboard has a Collaborate tool which allows the sharing of your screen and useful student participation (such as polls and emojis for instant feedback). It also permit breakout rooms so that students can do group work (see here for an instructional video).

- A Zoom call (see Danna Youg’s twitter thread for a guide, and Stanford’s advice on how to use it effectively).

The main difficulty of live teaching virtually is:

- Ease of distractions for students, and lack of physical cues around engagement

- Lack of a decent sized whiteboard and physical representation of idea formation

- Weird management of energy levels

The upsides of live teaching virtually are:

- No commuting (making it possible/easier for people in different time zones)

- Use of breakout rooms is quicker and easier than physical spaces

- Easy integration of online polling or collaborative whiteboards (e.g. Mural)

Model 3: Remote classroom

Remote classrooms use the technology of the internet to distribute content but don’t fundamentally differ from a distance degree. The key value provided by the university is therefore the grading of assignments and student feedback. They are paying not for the content per se, but to have a professional instructor grade it for them. Automated quizzes don’t cut it in this context. Examples:

- Open University

- The Managerial Economics course that I delivered for the ESCP EMIB

Model 4: The watcher

This is when a physical course is delivered as normal but participants receive remote access. This has a bigger emphasis on hardware needs (e.g. high quality cameras and mics throughout the audience) and editing. But it’s an easy way to grant access to those unable to attend physically. Some examples:

Of course some courses can combine the above within a single course. I think for all serious online courses (i.e. ones where students pay big money to a reputable institution), the key factors for success:

- Strict schedule

- Tough assessments

I see a major advantage for online courses being the opportunity to crowdsource and aggregate grading into quick, responsive, 360 feedback. I like to ensure that students are viewing, and critically engaging in each others submissions.

Here are some key resources that I have utilised:

- An exceptional collection of tips and insight on online learning is: https://community.mru.org/

- Harvard Business Publishing have a couple of useful articles: 8 tips for teaching online and How to quickly adapt to teaching online.

- This twitter thread by Luke Stein is a great resource.

Here’s a list of companies that I’m keeping an eye on:

I have taken, and recommend, the following online courses:

- The Modern World, Part One: Global History from 1760 to 1910, Philip Zelikow, University of Virginia, Coursera

- The Threat of Nuclear Terrorism, William J. Perry, Stanford Online

- Economic History of the Soviet Union, Guinevere Liberty Nell, Marginal Revolution University

Also, I really like the look of these:

- Principles of Economics, John Taylor, Stanford, edX

- Chicago Price Theory, Kevin Murphy, YouTube

- Financial Markets, Robert Shiller, Yale, Coursera

- Capitalism and Political Economy, Mike Mungar, Duke

- The Making of Modern Ukraine, Timothy Snyder, Yale

It’s never been easier to learn online, and it’s never been easier to teach online. Experiment and have fun!

Note: this article has been routinely updated since it was first published