Behavioural economics

| Lecture handout: Behavioural economics* |

Textbook Reading: Chapter 11

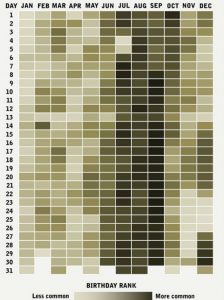

Here is an explanation of the Birthday Paradox (and here is an intuitive proof). Notice that the probability calculation assumes a uniform distribution (i.e. that there’s a 1/365 chance of being born on any given day). In fact, birthdays in July, August and September are more common than other months.

This applet allows you to play multiple games of the Monty Hall problem. An article in the Smithsonian Magazine asks “When Did Girls Start Wearing Pink?”

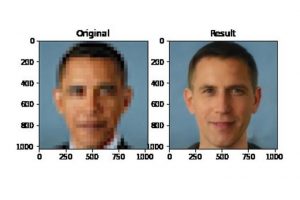

I used a pixelated image for an example of confirmation bias, and so I found it very interesting to see this example of bias contained within AI trained super resolution:

Here is more on the McDonald’s case:

- “The Truth Behind the Infamous McDonald’s Hot Coffee Case” By A.J. Serafini, Poole Law Group

| Case: “Sun: A CEO’s Last Stand”, Business Week, July 26th 2004 (£) |

| Instructor Resource: A List of Behavioural Anomalies, March 2011 |

| Activity: Complete this Sun Microsystems quiz |

The identification of behavioural anomalies has often been used as a justification for government intervention. But as Mike Munger warns,

“Every flaw in consumers is worse in voters”

Therefore we should be skeptical of fixing market failures through democracy.

Recommended books:

- Poundstone, William (2010) Priceless: The Hidden Psychology Of Value Oneworld

- Kahneman, Daniel (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow Farrar Straus and Giroux

Recommended articles:

- Lambert, Craig “The Marketplace of Perceptions”, Harvard Magazine, March-April 2006 – A summary of chief insights from behavioural economics and neuroeconomics

- Poundstone, W., (2011) “Prospect Theory” (Chapter 16) and “Ultimatum Game” (chapter 18) from Priceless: The Hidden Psychology of Value, One World – Good introductions to key concepts

- Tabarrok, A., “A Phool and His Money” Review of PHISHING FOR PHOOLS: The Economics of Manipulation and Deception, by George A. Akerlof and Robert Shiller, Princeton University Press – A defence of standard economic theory against behavioural claims

Investing

I recommend this interview with Bill Ackman:

- #413 – Bill Ackman: Investing, Financial Battles, Harvard, DEI, X & Free Speech, Lex Fridman – he talks about the influence of Benjamin Graham’s ‘The Intelligent Investor’ as well as the career of Warren Buffet. I like thee point about how stock markets are betting machines in the short term but weighing machines in the long term (i.e. they reveal the truth).

| Learning Objectives: Apply a range of examples of behavioural anomalies to real business situations. Understand behavioural anomalies in light of an ecologically rational framework. |