Personal finance MOT

In a field one summer’s day a Grasshopper was hopping about, chirping and singing to its heart’s content. An Ant passed by, bearing along with great toil an ear of corn he was taking to the nest.

“Why not come and chat with me,” said the Grasshopper, “instead of toiling and moiling in that way?”

“I am helping to lay up food for the winter,” said the Ant, “and recommend you to do the same.”

“Why bother about winter?” said the Grasshopper; we have got plenty of food at present.” But the Ant went on its way and continued its toil.

When the winter came the Grasshopper had no food and found itself dying of hunger, while it saw the ants distributing every day corn and grain from the stores they had collected in the summer. Then the Grasshopper knew: It is best to prepare for the days of necessity.

Source. (See Martin Wolf’s re-telling of the Ant and the Grasshopper as a modern fable here).

I endorse Chris Dillow’s four general principles of investing:

- Live within your means. The safest way to get rich is to save. How you invest your savings – cash, shares, gold, whatever – is a secondary consideration, unless you are really silly.

- Minimize taxes and charges. Most people can save tax-efficiently through ISAs and pensions, and should do so. Also, don’t be tempted by high-charging funds – they are usually not worth it. And if you hold shares directly, don’t trade much.

- Remember that high prices, on average, mean low expected returns. Don’t jump on bandwagons.

- Remember G.L.S Shackle’s words: “knowledge of the future is a contradiction in terms.” Don’t pretend you can see what’s coming. And don’t pay others in the belief that they can do so. The essential fact about the financial world is risk (and/or uncertainty). The key question is: what risks are you prepared to take, and which aren’t you? This paper by John Cochrane discusses this well.

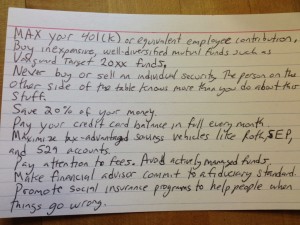

I like Harold Pollack’s attempt to put financial advice on a 4×6 index card:

Photo by Harold Pollack

I recommend this investment philosophy from Jim O’Shaughnessy.

And I enjoyed listening to Bill Ackman channel his inner Warren Buffett to explain his approach to (and his defense of) activist investing: #413 – Bill Ackman, Lex Fridman podcast, February 20th 2024.

Many people will say that they want to take more control over their current spending and future financial security, but often find it difficult to actually achieve this. I’m not a qualified financial adviser, I can’t demonstrate past success at investment decisions, and I do not encourage you to blindly follow my advice. All I can offer is a process by which you can gain a better understanding of your personal finances, and something that seems to work for me.

You probably don’t have time to follow these steps now. So find a date a few weeks or months from now and put it in your diary. Don’t shift it. Treat this seriously. Do it when you have time…

Preamble

Picture yourself at 65, and make it as vivid an image as possible – not so much what you look like, more where you are and what you are doing (for more on this approach see Chapter 9 of this book). A large reason why people are careless with their financial situation (and constantly undermine their future happiness) is because we’re conditioned to focus on immediate rewards. But we need to shift perspective and think about what actions your present self needs to take in order to make your future self happy. What resources do you need to deliver to your 65 year old self? Picture your children at 20. What do you want to be able to give them? Having to adjust your future goals to meet your financial resources is failure. Adjust your present behaviour to hit your targets.

Practice self-control and delayed gratification. If you want to watch a movie, try waiting a few days. Treat it as a reward.

In

- Go through your last 6 payslips and use your typical (i.e. not including bonuses) net (i.e. after tax) income. Unless bonuses are a significant part of your regular income then treat them as a bonus and save them.

Out

- The only outgoings I measure are household bills. To do this I check all of my direct debits and fill in a summary sheet (download a PDF here). If I have a DD I put the amount in the “monthly DD” column. If I pay it annually I put it in the “annual” column and then write the month in which it is paid in the “Month” column next to it. Ideally these are spread out throughout the year. The spreadsheet will automatically calculate the “annual sum” and then there are two figures for “monthly sum”, which are the total of all the monthly DD payments and the total of the annual payments divided by 12. Finally, the “monthly total” is the sum of those two numbers, revealing how much I spend on household bills, on average, every month.

- My wife and I use our joint account for those bills and only those bills. I make sure that we have a standing order that exceeds this amount going in at the beginning of each month.

- In addition to household bills our main spending areas are: food, petrol, commuting, clothes, other. I am fortunate enough to not have to keep track of these, however if I did I would use the budget feature in Monzo to do so.

Shake it all about

- Once a year I update an overview of my net wealth (download a PDF here).

- If like me you’re lucky enough to own your own home, this is likely to be the biggest component, and I use a rough estimate of the market price less the outstanding mortgage. I own shares in 2 companies and list these based on the current share price. The investment ISAs include managed funds as well as an easy access Vanguard account. (If it takes a long time to find a current balance then perhaps that’s a problem. But then again, if you’re checking them more than once a year that may also be a problem. You want to “Set it, and forget it“.) We have savings pots in our Monzo accounts for things like holidays and the sum of those 5 categories is what I consider to be my net wealth. A decent proportion of net wealth is pensions and this can be hard to measure, but most providers will show a current value. Make sure you max out any matched contribution and have a figure as hugh as you can afford (>25%). Below that, I include the balance of my children’s Junior ISAs which is nice to know, but not “our” wealth.

- I don’t include the balance of current accounts because these tend to be low and volatile. Monzo pots have been a real help to allocate specific spending commitments, such as holidays, Christmas, kids extra-curricular activities, car maintenance, house maintenance, and vets bills.

Some general comments:

- Get a good credit card. Make sure you pay it off each month but make sure you’re getting rewards for spending. An easy way is to link it with Airmiles.

- For advice on what type of pension, life insurance, and savings vehicle are appropriate for you consult a professional financial advisor (this is helpful). If you don’t think it’s worth paying a few hundred quid to sort out your financial future then you’re an irresponsible idiot!

- It is really important to start saving early. “Someone who starts saving at the age of 21 and then stops at 30 will end up with a bigger pension pot than a saver who starts at 30 and puts money aside for the next 40 years until retiring at 70“. Also look at the calculators here.

- Have a look at the interest rates you’re paying. Make sure that you pay off your most expensive loans first.

- Act as though the Efficient Market Hypothesis is true (see the second half of this page). The best investment strategy is a low cost well diversified index fund. Vanguard are the original and remain the best (and even after the turmoil in Spring 2020, if your goals are long term you shouldn’t even be looking at it). I use the FTSE Global All Cap index, although

- The ESG Developed World All Cap Equity Index Fund is very similar but reduces emerging market risk (I think).

- The Lifestrategy 100 is more UK based, which reduces exchange rate risk.

Student loans

I didn’t have a student loan and know they’re controversial, but according to Martin Wolf (2023, p. 285) in an ideal world…:

- Lower fees (£9k is too high)

- An equity component to the contract such that higher earning students pay more than their loans

Finally

This advice for personal financial can be extended to life more generally. Here’s an example of a pre-mortem for personal decisions: